Is Your Blockchain Invention Patentable?

Co-authored by Siddharth Bhardwaj, Summer Associate 2024.

Blockchain is becoming central to more FinTech patent portfolios than ever – but it’s harder to obtain protection on blockchain than most other technologies. The US Supreme Court’s decision in Alice v. CLS Bank (2014) strengthened limits on what subject matter is eligible for patent protection under 35. U.S.C. §101. Today’s software-based technologies do not always pass Alice’s multi-part test for excluding “abstract ideas” from patentability. Enterprises developing blockchain technology are often left with questions as to whether their core inventions can be protected. This article explains our approach to answering these questions.

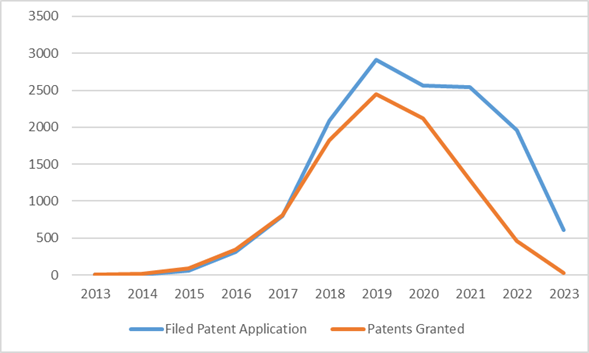

The good news is that well-drafted blockchain patent applications can and do pass muster at the United States Patent & Trademark Office (USPTO). In the last ten years, almost 14,000 blockchain-based patent applications have been filed, and almost 10,000 blockchain-based patents have been issued.

We’ll begin with a “deep dive” into the Alice-Mayo test outlined in USPTO’s 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance as it applies to blockchain claims. In Section II we analyze the current blockchain patent landscape to identify trends in the filing and issuance of blockchain patents. Finally, in Section III we provide some practical tips for drafting patent applications that are likely to yield strong protection and boost the value of a FinTech enterprise developing blockchain technology.

I. ALICE-MAYO TEST OF PATENT ELIGIBILITY

Alice rendered abstract ideas implemented on a generic computer to be patent ineligible and created obstacles to obtaining patent protection on computer software such as blockchain. In the wake of the decision, the USPTO issued several examination guidance documents including the 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance (“Guidance”). The Guidance provided clarification on patent eligibility of certain groups of abstract ideas, such as “mathematical concepts,” “certain methods of organizing human activity” and “mental processes.” These are examples of categories excluded from patentability by courts and are known as “judicial exceptions” to patentability. The Guidance outlined the Alice-Mayo test (based on Supreme Court’s decision in Alice and the related Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc.) which included a two-prong inquiry for determining whether a claim is “directed to” a judicial exception.

The first step of the Alice-Mayo test (Step 1) of the patent eligibility analysis is an inquiry as to whether the claim of the patent application is directed to a process, machine, manufacture or composition of matter. If the answer is no, the claim is considered patent ineligible. If the answer is in the affirmative, then the test proceeds to the second step (Step 2) of patent eligibility.

Step 2 includes two sub-steps, step 2A and step 2B. Step 2A is an inquiry as to whether the claim is directed to one of the patent-ineligible judicial exceptions -- in the case of software inventions, an “abstract idea”. If the claim is not directed to an abstract idea, the claim qualifies as a patent eligible subject matter. However, just being “directed to” an abstract ideadoes not doom claim eligibility. Instead, Step 2B is an inquiry as to whether the claim recites additional elements that amount to “significantly more” than the abstract idea. In other words, step 2B is an inquiry as to whether the claim provides for an inventive concept by adding limitations beyond an abstract idea that is not well-understood, routine, conventional. If the claim recites additional elements that amount to significantly more than the abstract idea, then the claim qualifies as patent eligible.

The main clarification provided by the Guidance is to set forth a two-pronged analysis under step 2A. Prong 1 asks whether the claim recites an “abstract idea.” Prong 2 is an inquiry as to whether the claim recites additional elements that integrate the abstract idea into a practical application. The rationale behind prong 2 is to determine whether the claim applies, relies on, or uses the abstract idea in a manner that imposes a meaningful limitation on the abstract idea, such that the claim is more than a drafting effort designed to monopolize the abstract idea. It should be noted that according to the Alice-Mayo test, “reciting” an abstract idea is different from being “directed to” an abstract idea. A claim that recites an abstract idea simply includes an abstract idea. But in order to be “directed to” an abstract idea, the claim must fail both prong 1 and prong 2 of step 2A.

Determining whether the claim recites additional elements that integrate the abstract idea into a practical application under prong 2 involves (a) identifying whether the claim includes additional elements reciting elements beyond the abstract idea, and (b) evaluating the additional elements both individually and collectively to determine whether they integrate the exception into a practical application, or uses the abstract idea in a manner that imposes a meaningful limit on the abstract idea, such that the claim is more than a drafting effort designed to monopolize the abstract idea.

II. BLOCKCHAIN PATENT LANDSCAPE ANALYSIS

13,854 patent applications on blockchain technology were filed & published at the USPTO between January 2013 and October 2023. During this time, 9,442 blockchain patents were granted.

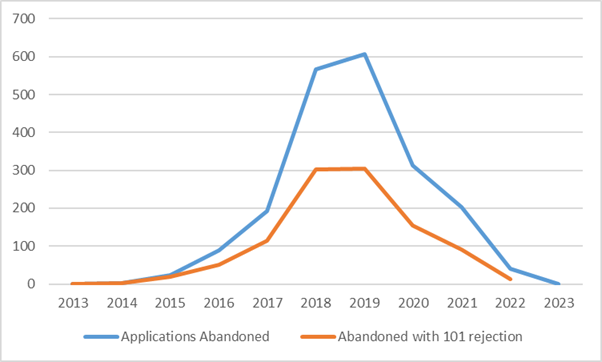

In the period between 2015 and 2019, there was an increase in both the number of filed blockchain patent applications and the number of issued blockchain patents. The first period was followed by a second period between 2019 and 2022 where the number of filed applications plateaued while the number of issued patents decreased. About 1160 filed applications were abandoned during the second period, and 560 of the 1160 abandoned applications faced rejections based on §101 by the USPTO (as shown in FIG. 2).

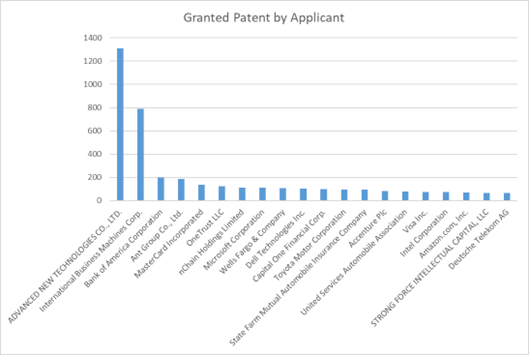

In terms of patent applicants, Advanced New Technologies has been issued the greatest number of blockchain patents in the US (1311 patents), followed by IBM (790 patents), Bank of America (198 patents), Ant Group Co. Ltd.[1]/ (188 patents), Mastercard Inc. (137 patents) and One Trust LLC (123 patents).

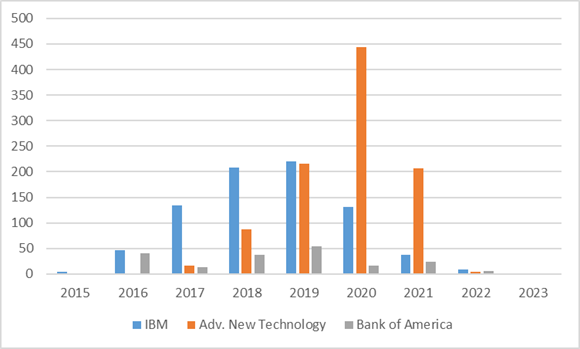

The top three U.S. blockchain patent holders are Advanced New Technologies, IBM and Bank of America. For patent applications filed between 2016 and 2019, IBM was issued the highest number of blockchain patents. The number of blockchain patents issued to Advanced New technologies based on applications filed since 2017 has exceeded IBM.

Blockchain patent applications filed since 2021 are still likely undergoing prosecution before the USPTO, and therefore many of these applications have not been issued yet.

III. PRACTICAL TIPS FOR PROSECUTING BLOCKCHAIN APPLICATIONS

Although the Alice-Mayo test initially rendered many software-related inventions as unpatentable, the outlook for patentability of blockchain patent applications has improved in recent years. In the last decade, close to 10,000 blockchain-related patents have been issued. However, we advise applicants seeking protection for their blockchain technology that the claims and specification of their patent applications should be drafted with the Alice-Mayo test in mind.

Tip 1: Resolve 101 issues with the Examiner.

The first key takeaway from our findings is that the applicants are better off resolving an Alice/§101 rejection with the patent examiner rather than appealing to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). We identified a total of 38 blockchain-related patent applications in which an applicant appealed an examiner’s §101 rejection. The search resulted in 38 appeals. In only four of the 38 appeals, the PTAB reversed the examiner’s §101 rejection -- put another way, the PTAB affirmed the examiner’s §101 rejection about 90% of the time. In three of the four reversals, the PTAB issued new grounds for a §101 rejection. As a result, only oner of the 38 appeals succeeded in overcoming a §101 rejection at the PTAB -- a failure rate of 97.3%. We note that of the 37 appeals that failed to overcome the §101 rejection, 5 applications were later allowed based on claim amendments before the examiner. It is clear that a strategy of working with the examiner to resolve an Alice/§101 rejection in a blockchain patent application is far more likely to result in an issued patent.

Tip 2: Do not concede that a blockchain claim is “directed to” an abstract idea.

The second key takeaway is that applications should be drafted with an eye on prong 2 of step 2A because it is highly unlikely that blockchain claims will be considered patentable under prong 1 of step 2A (i.e., found to not “recite” an abstract idea). Of the 38 appeals that we analyzed, the claim was found to recite an abstract idea (e.g., methods of organizing human activity such as commercial activities that can be performed in the mind) in every case. Within the prong 2 analysis, the PTAB typically asks two separate questions: 1) Does the claim include additional elements besides the abstract idea? 2) Do the additional elements integrate the abstract idea to a practical application? If the PTAB finds that there are no additional elements besides the abstract idea, the claim typically will be deemed ineligible under the Alice-Mayo test.

To ensure that the claim recites additional elements with the meaning of prong 2 of step 2A, patent applicants are strongly advised to include substantial details about the technical operations of their invention in the claims. While this may make the claims longer and potentially narrower in scope, it will likely improve the chances of overcoming the first question under the prong 2 analysis. This advice is supported by the five appeals (of the 38 appeals noted above) in which the PTAB affirmed an examiner’s 101 rejection, but the corresponding applications were later issued based on claim amendments made by the applicant. In these five cases, the average length of claims found patent ineligible by PTAB was 150 words, while the average length of claims ultimately allowed was 319 words.[2]/

Tip 3: Integrate blockchain concepts into a practical application.

Finally, applicants should ensure that the additional technical elements integrate the abstract idea to a practical application. The PTAB has deemed improvements in technology rather than improvements in the abstract idea to constitute integration of an abstract idea into a practical application. For example, PTAB has deemed that a novel abstract idea implemented on a generic computer is still an abstract idea.[3] Applicants should consider implementing functionality into their claims that cannot be carried out by the human mind even if hypothetically given a substantial amount of time.[4] In blockchain claims, this may include adding claim limitations that relate to technical concepts such as hashing or verifying digital signature that are impossible for a human mind to accomplish.

CONCLUSION

The data show that blockchain inventions make up a sizable portion of technology patent portfolios, and a patent application relating to blockchain technology can be positioned for success at the patent office by following our approach outlined above. We at Mintz are ready to assist your enterprise in evaluating the best IP strategy for your blockchain inventions.

[1]/ Ant Group Co. Ltd is an affiliate of Advanced New Technologies.

[2]/ In a future article, we will discuss appeals to the PTAB: one where the PTAB reversed a patent examiner’s §101 rejection and the other where the PTAB affirmed patent examiner’s §101 rejection but the rejected claims were later allowed after claim amendment.

[3] See p. 11, Appeal Decision dated November 4, 2021 of ‘0030 Application (citing Synopsys, Inc. v. Mentor Graphics Corp., 839 F.3d 1138, 1151 (Fed. Cir. 2016))

[4] See p. 18, Appeal Decision dated August 19, 2020, of U.S. Application No. 14/719,030.

Author