UPC Risks Unveiled: Navigating Outcome Trends and Parallel Revocation Strategies

The Unified Patent Court (UPC) is transforming the way patents are enforced and challenged in Europe with its broad jurisdiction and potential for harmonizing the patent enforcement situation in a significant part of the European Union. With 18 member states, the UPC provides a streamlined and centralized forum for handling patent disputes on both validity and infringement for those countries that have acceded to the UPC agreement. This innovative structure aims to provide businesses and patent holders with a more efficient system, reducing the complexity and cost of dealing with patent disputes across diverse legal systems. At a little more than a year and a half since its inception, the UPC is becoming an increasingly relevant part of a global patent enforcement strategy, and the team at Mintz has hands-on experience navigating this new court system. Whether you are defending a patent or challenging one, we’ve been there, seen it, and we are helping shape the outcomes in this rapidly-evolving landscape.

In this article, we’ll cover some strategy trends that are beginning to emerge, including a somewhat unexpected option for a defendant in an infringement case to challenge the validity of an asserted patent before two different UPC courts in parallel. As we’ll explain in further detail below, the outcomes of the few cases in which defendants utilized this strategy have so far resulted in a win for the infringement action claimant – the asserted patents have been maintained and found to be infringed even with dual validity attacks before two UPC first instance courts. Furthermore, while some early decisions on validity in revocation actions brought before the central divisions of the UPC have resulted in the attacked patents being revoked, a closer look at the data, taking into account the full background of those revoked patents, shows that the UPC continues to be a generally patentee-friendly venue.

Brief Overview of the UPC

The UPC’s member states include Germany, France, and Italy and collectively cover about 80% of the European Union’s gross domestic product (GDP)[1]. Prior to the UPC opening for business on June 1, 2023, the German patent enforcement system’s established reputation for rapid and predictable proceedings made it the most attractive venue for patent holders looking to enforce their patent rights. The German system features a bifurcated system: infringement proceedings to determine liability of the defendant and nullity proceedings to determine the validity of an asserted patent and heard before two different courts. In many cases, the infringement proceedings outpace the nullity proceedings, such that damages or even an injunction against the defendant might occur months or even years before the validity of the patent is decided.

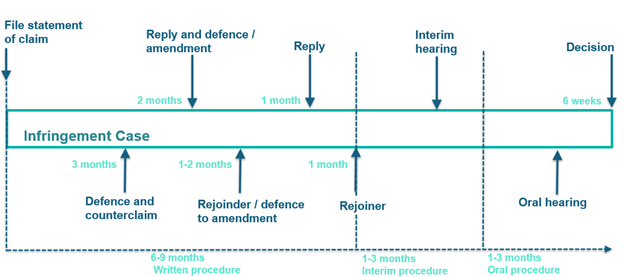

The UPC, on the other hand, was designed as a one-stop shop for both infringement and revocation cases, advertising a rapid and unified solution for resolving patent infringement and validity issues in a single proceeding, with a target timeline of 12-15 months from complaint filing to written decision on both issues. This accelerated timeline can generally apply significant pressure on a defendant, particularly one who is caught by surprise. Infringement cases are heard in a local or regional division[2] where the alleged infringing action occurred (or is continuing or threatened to occur) or where the defendant has its residence or principal place of business. If the defendant has no residence or place of business within a UPC member state or if the UPC member state in which infringement is alleged has no local or regional division, an infringement action may be brought before a central division.[3] Actions for revocation or noninfringement (which can be thought of as analogous to declaratory judgement actions in the U.S., although there is no requirement that the patentee must have threatened an infringement suit against the party bringing the revocation) are brought before a central division that has proper subject matter competence.[4]

Parallel Revocation Strategy

The UPC Rules of Procedure state that a counterclaim for revocation in response to an infringement action between the same parties regarding the same patent will be heard in the same local division as the infringement action unless the local division refers either the validity action or the whole action to the central division or the parties agree to transfer the case. However, as we will explore in this article, some defendants in local division infringement actions have begun to explore a strategic approach involving a second validity attack at a central division in parallel the counterclaim for revocation filed at the local division.[5] This strategy involves a subsidiary or affiliate of the defendant in the local division infringement case bringing a standalone revocation action against the asserted patent, which has so far been allowed by the UPC due to a very narrow interpretation of the “same party and same patent” requirement for a counterclaim for revocation to be brought before the local division that is handling the original infringement action.

A standalone revocation action brought before a central division with a sufficiently short delay (i.e., less than 2-3 months) after initiation of an infringement action at a local division can, due to the shorter procedural schedule of the central revocation action, reach a validity decision prior to the combined infringement and validity decision at the local division. At a minimum, this parallel attack strategy can present the claimant in the local division infringement action with the necessity to defend the validity of the asserted patent before two different panels of judges.

Procedural Comparison with Oppositions at the EPO

To date, 635 cases have been filed at the UPC, with 239 of these cases being infringement actions filed before the Court of First Instance (CFI) and the majority being heard in German local divisions. Out of these 239 infringement actions, 132 have included a counterclaim by the defendant for revocation of the patent filed at the local division where the infringement action was brought. While infringement actions have so far been the most common use for the new court system, 55 standalone revocation actions have been filed before the Central Division, with the majority (40 of the 55) being before the Paris Central Division.[6]

While the local and regional divisions at the UPC play a significant role in patent enforcement and, as a consequence, in validity assessment for asserted patents, the central divisions are tasked primarily with handling standalone revocation proceedings, focusing on invalidity challenges, which can be based on substantive grounds such as added matter, insufficiency of disclosure, and lack of novelty and/or inventive step. In this manner, the UPC’s central divisions provide an additional path to the European Patent Office’s (EPO’s) opposition division for invalidating a European patent that has not opted out of the UPC’s jurisdiction.

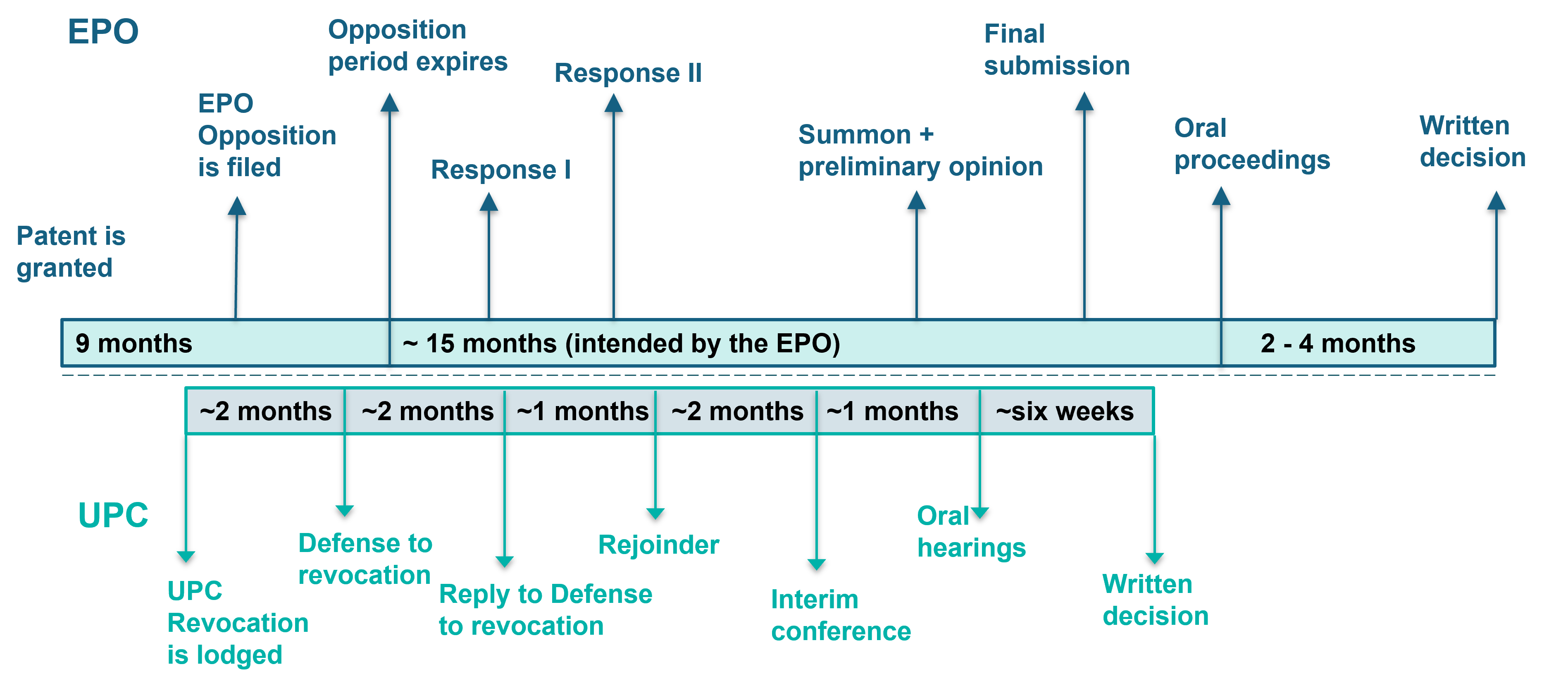

While EPO oppositions are a well-established process for challenging European patents and are, like UPC revocation actions, inter partes proceedings, there are important differences. An opposition must be filed within 9 months of the grant date of the patent, and the validity attacks by all opponents who file an opposition during the opposition period are handled in a combined written and oral proceeding. UPC revocation actions can be filed at any time during the term of the patent, and even after expiration (e.g., to defend against a potential claim for back damages for activities occurring prior to patent expiration), and are one to one proceedings – if multiple claimants file concurrent revocation actions against a single patent, the patentee can be required to defend against each claimant in a separate written and oral proceedings unless the parties agree and/or the court decides to consolidate multiple actions. Oppositions typically take 18 months or even longer from the end of the opposition period to a first instance decision on validity. The UPC, on the other hand, aims to provide decisions within 12 months from filling – clearly a faster resolution than the EPO even when real-world timelines have slipped to longer than the advertised schedule.

|

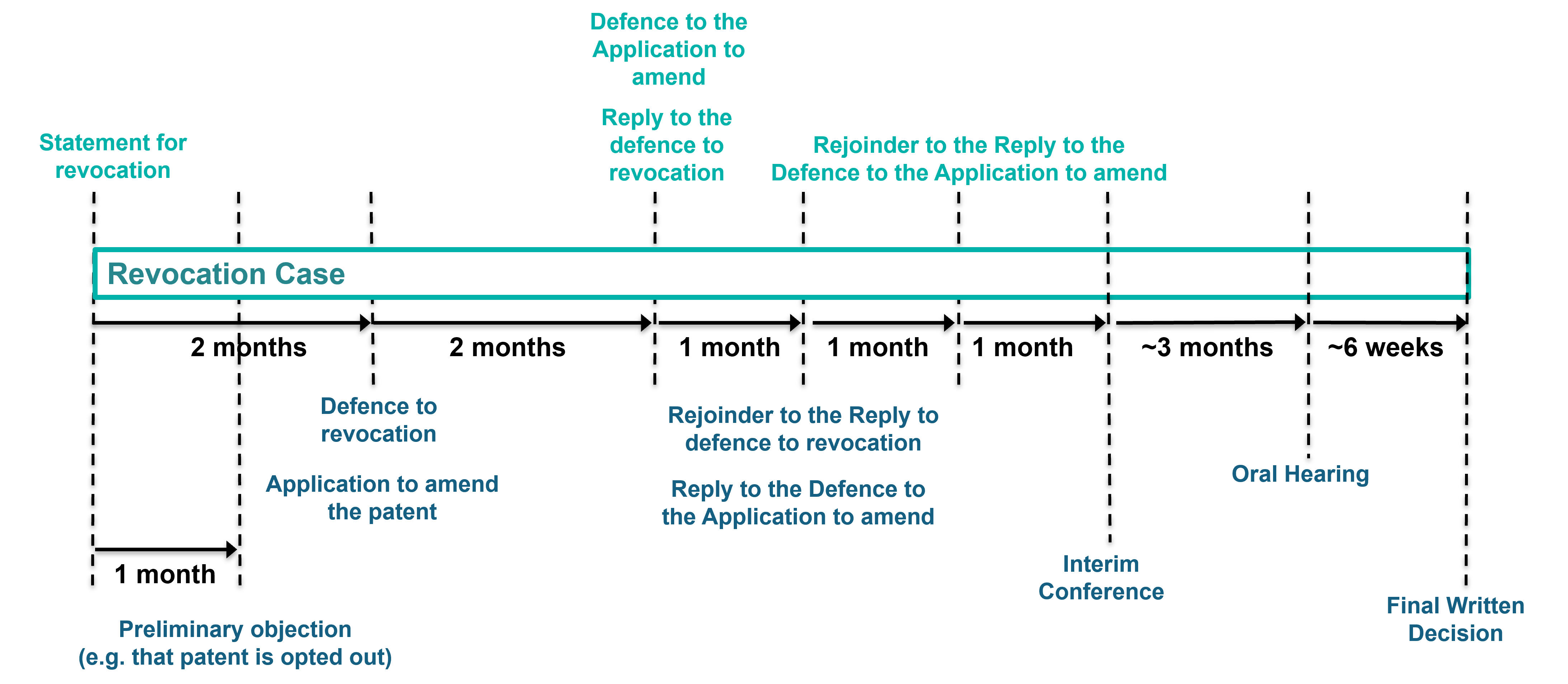

As noted above, the rapid pace of the UPC means tight deadlines and limited time for a defendant to prepare when faced with an unexpected infringement suit. The below timelines illustrate these tight deadlines that are imposed by the 12-month timeline.

|

|

Strategic Advantage to Parallel Revocation Proceedings

The use of two simultaneous revocation fights – one at the local division and one at the central division – could theoretically provide a strategic advantage to an accused infringer. This dual approach provides two opportunities for success, but also presents the potential risk of conflicting decisions from different divisions. The deadlines imposed by the UPC are tight in order to reach a decision within the intended 12-month time period. If an accused infringer acts quickly and files a standalone revocation action at the central division shortly after being served with an infringement complaint at the local division, the central division could potentially reach a decision prior to the local division, thus resulting in a revocation ruling prior to an infringement hearing. While it may seem daunting to face two simultaneous revocation challenges, outcomes thus far suggest that the risks to well-selected patents are not significantly increased by the use of the parallel central division attack strategy.

The first test of this strategy was a case in which Edwards Lifesciences Corporation brought an infringement action against Meril Life Sciences Pvt. Ltd. (Meril India) and its subsidiary Meril GmbH (Meril Germany) in the Munich Local Division. Just over two months after the infringement action commenced, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Meril India, Meril Italy Srl, commenced a revocation action in the Paris Central Division against the same patent involved in the pending infringement action.[7] In response to the revocation filing at the central division, Edwards alleged that Meril was attempting to interfere with the pending infringement proceedings which would risk different outcomes with respect to the same patent. The judge-rapporteur, however, concluded that Meril Italy and Meril India are in fact different parties under the literal interpretation of Article 33(4) of the UPC Agreement and allowed the parallel revocation cases to proceed. While this case can be seen as paving the way for bifurcation, the outcomes in the revocation cases at both the local and central divisions ultimately results in the patent being upheld in an amended form. Even though Meril essentially took two swings at invalidating the asserted patent, it proved to be strong enough to withstand multiple revocation attacks.

Whether this tactic actually does become an advantageous approach remains to be seen. As of December 2024, only 10 of the 38 standalone revocation cases pending at a central division currently have a parallel pending counterclaim for revocation at a local division. Those 10 pending cases, however, account for less than 5% of the pending infringement actions at local divisions as of December 2024.[8]

Outcome Trends: UPC versus EPO

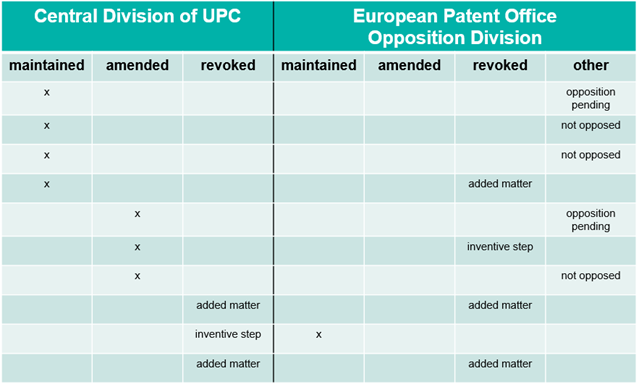

The Mintz team has observed firsthand interesting trends of revocation actions at the Paris Central Division of the UPC and EPO oppositions based on recent decisions. In these early decisions, the patents faced common challenges of added matter and lack of inventive step at the UPC and the EPO.

In short, the UPC has not demonstrated a significantly different approach to added matter relative to the EPO’s Opposition Division. First instance outcomes available to date indicate that patents revoked for added matter at the UPC have also been successfully attacked on similar grounds in an EPO opposition. It remains uncertain whether the UPC will continue to follow a similar approach to the EPO opposition division regarding added matter, in particular because of how few appellate decisions on these issues have been rendered, such that the first instance courts are largely left to decide what standards and tests for validity should be applied.

|

In contrast, the central division of the UPC has shown a slightly less patentee-friendly approach to inventive step relative to the EPO opposition divisions, having thus far maintained most patents under such an attack at least in an amended form. With the understanding that data points are still limited, the current outcomes underscore the importance of preparing robust prior art fallback positions, particularly in the originally granted dependent claims or through well-supported auxiliary requests. This strategy entails understanding the existing prior art and developing dependent claims or auxiliary requests that address various potential attacks that an infringement defendant or a revocation action claimant might bring. By thoughtfully drafting dependent claims or auxiliary requests that cover different aspects of the invention, a patent holder can strengthen their position in demonstrating the invention’s novelty and inventiveness in several key areas. This approach also minimizes the chances of an opponent successfully exploiting potentially weak points in the patent. Ultimately, this preparation also enhances the patent holder’s position in settlement negotiations by emphasizing the patent’s strength.

The new strategy of parallel revocation proceedings at the UPC also opens the door to the possibility of a trifecta of challenges if a patent is also within the opposition window (nine months from grant). The UPC rules of procedure allow for a stay if an opposition decision is imminent. However, this rule has so far been applied quite narrowly, with the UPC declining to stay proceedings without consent of both parties in cases in which the revocation action schedule is likely to result in a first instance decision prior to the end of the full opposition process, including possible appeals. That said, if a defendant in a UPC infringement action has the option of either filing an opposition or joining an ongoing opposition brought by other opponents (which is allowed under EPO opposition rules), this presents an additional opportunity to complicate the validity case for the patentee. The tight deadlines imposed by the UPC and the possibility of a triple threat highlight the importance of strategic planning and the ability to react quickly to potential revocation challenges by having advanced preparation, awareness of prior art, and focusing on patents that have demonstrated strength in the EPO’s examination process and for which viable validity fallback positions are available to address all avenues of potential attack.

While the UPC is still in its early stages, its potential as an influential forum for patent disputes is becoming increasingly clear. As the system evolves, it will be crucial for stakeholders to stay proactive and strategic. Success at the UPC will depend not only on a solid understanding of its procedural nuances but also on strategic case preparation. Whether defending patent rights or challenging them, those who are able to adapt to the UPC’s dynamics and leverage its opportunities will likely be well positioned to successfully navigate its complexities and achieve favorable outcomes. Mintz and our partner firms practicing before the UPC are on the cutting edge of these developments.

[2] Local divisions of the UPC are currently seated in Austria (Vienna), Belgium (Brussels), Denmark (Copenhagen), Finland (Helsinki), France (Paris), Germany (Düsseldorf, Hamburg, Mannheim, and Munich), Italy (Milan), Portugal (Lisbon), Slovenia (Ljubljana), and The Netherlands (The Hague), with a regional division in Stockholm serving the Scandinavian and Baltic member states.

[3] Central divisions of the UPC are currently seated in Paris, Milan, and Munich.

[4] The Paris Central Division handles revocation actions for patents relating to International Patent Classification (IPC) sections B, D, E, G, and H (performing operations, transportation, textiles, paper, fixed constructions, physics, and electricity) as well as those in IPC sections A (human needs such as agriculture, food products, tobacco, clothing, jewelry, furniture, sanitary items, and entertainment) and C (chemistry and metallurgy) that have a supplementary protection certificate (SPC) covering an active ingredient in a product (including uses and methods of manufacture). The Munich Central Division handles patents in IPC section F (mechanical engineering, lighting, heating, weapons, explosives) and those in section C without SPCs, while the Milan Central Division handles patents in IPC section A without SPCs.

[5] UPC Rules of Procedure (RoP), Article 33(3) and 33(2) of the Unified Patent Court Agreement (UPCA)

[6] Case Load of the Court Since Start of Operation in June 2023

[7] Edwards Lifesciences Corporation European patent EP 3646825