SEC Approves Sweeping New Climate Disclosure Rule: Key Takeaways

The Securities & Exchange Commission ("SEC") issued its long-awaited final rule concerning climate disclosures, entitled “The Enhancement and Standardization of Climate-Related Disclosures for Investors” (“Climate Disclosure Rule”), on March 6, 2024. This rulemaking is the first prescriptive regulation on a national scale mandating disclosures of climate-related information by US capital markets participants.

The key elements of the Climate Disclosure Rule include:

- Disclosure of Climate-Related Material Risks and company efforts to mitigate or adapt;

- Disclosure of Scope 1 and Scope 2 Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions[1] for large accelerated filers and accelerated filers;

- Incorporation of Climate-Related Disclosures in Annual Reports filed with the SEC; and

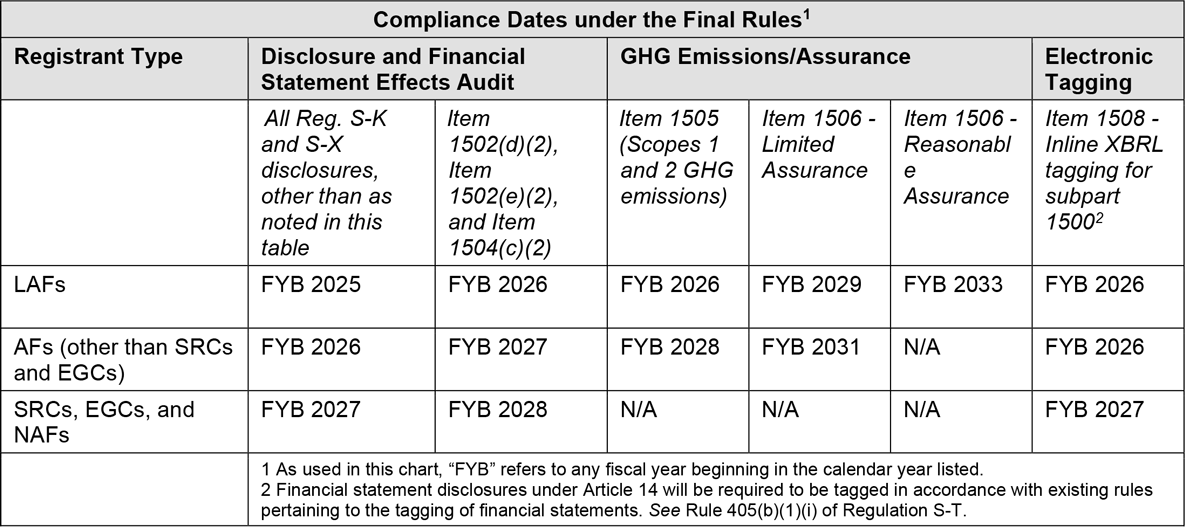

- Phased-in Implementation Schedule extending from FY 2025 to FY 2033.

While there are noteworthy exceptions and exemptions to the Climate Disclosure Rule, as discussed further below, the significance of this SEC regulatory action should not be underestimated. The SEC — a financial regulator — has now adopted a regulation widely perceived to be focused on environmental issues that will impact most public companies doing business in the United States. The Climate Disclosure Rule will become effective shortly (60 days following publication in the Federal Register), barring court action from a case filed to block this regulation.

I. Background

The SEC’s climate disclosure rule was long-expected, and aligns the United States with other developed economies around the world, and indeed individual US states, in requiring businesses to make climate disclosures.

Over the past few years, there has been a sustained effort by a number of groups to compel mandatory climate disclosures, especially with respect to greenhouse gas emissions, as part of a broader movement to combat climate change. This emphasis on climate disclosures has also arisen outside of the regulatory sphere, as a number of prominent investment firms have also emphasized climate disclosure. Against this backdrop, the SEC’s adoption of a climate disclosure rule is unsurprising.

A number of other developed economies have already promulgated their own set of climate disclosure rules, which the SEC acknowledged in the final rule. In particular, on the international front, the SEC noted that “in 2022, the European Union [] adopted the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive [], which requires certain large and listed companies and other entities, including non-EU entities, to report on sustainability-related issues in line with the European Sustainability Reporting Standards.” And from a domestic perspective, the SEC summarized California’s recent regulatory initiative, stating that “California recently adopted the Climate-Related Financial Risk Act (Senate Bill 261), which will require certain public and private US companies that do business in California and have over $500 million in annual revenues to disclose their climate-related financial risks and measures” and “the Climate Corporate Data Accountability Act (Senate Bill 253), which will require certain public and private companies that do business in California and have over $1 billion in annual revenues to disclose their GHG emissions.” Based upon these regulatory developments, the SEC’s adoption of climate disclosures brings it within a broader regulatory trend.

A. Proposed SEC Climate Disclosure Rule (March 2022)

The SEC was one of the (comparatively) early adopters of this regulatory movement, as it published a draft climate disclosure rule on March 21, 2022. This draft rule, which was described as an attempt to “advance consistent, clear, intelligible, comparable, and accurate disclosure of climate-related financial risk,” was a centerpiece of the Biden administration’s environmental agenda.

However, this draft climate disclosure rule — which was notably more expansive than the final climate disclosure rule — provoked significant reaction (and frequently resistance) from a wide range of entities and individuals, likely contributing to the climate disclosure rule languishing on the SEC’s docket for nearly two years after it was announced.

B. Public Comments Received by the SEC

The public reaction to, and engagement with, the SEC’s draft climate disclosure rule was significant. The SEC received nearly 25,000 public comments by individuals and organizations from across modern American society. Few, if any, of the SEC’s rule proposals ever received such voluminous, significant, and diverse comments.

Notably, among the various proposals to adjust the draft climate disclosure rule that received significant support, the SEC ultimately adopted several, including: (1) removing Scope 3 GHG emissions (a position advocated by both supporters and opponents of the climate disclosure rule); (2) extending the phase-in period for compliance; and (3) adopting and applying the principle of materiality to these climate disclosures.

II. Final SEC Climate Disclosure Rule

The new Climate Disclosure Rule, while scaled back from the proposed initial version, is a substantial addition to corporate disclosure law. Its intended purpose, according to the SEC, is “to elicit more consistent, comparable, and reliable information for investors to enable them to make informed assessments of the impact of climate-related risks on current and potential investments.”[2] It seeks to accomplish this goal through a range of new disclosure requirements for companies concerning climate-risk, GHG emissions, and more. The Climate Disclosure Rule’s substantive requirements and definitions are modeled after guidelines issued by the Task Force on Climate Related Disclosures (“TCFD”), which issued a framework designed to elicit standardized information for investors to evaluate the climate risks facing companies.

The Climate Disclosure Rule specifically amends SEC Regulations S-K and S-X to require that companies disclose new climate information in their registration statements and annual reports. The following section describes these changes in more detail.

A. Disclosures

i. GHG Emissions

The Climate Disclosure Rule mandates that certain registrants report on their entity’s Scope 1 and Scope 2 GHG emissions metrics but does not require any filing entities to report Scope 3 GHG emissions. The SEC defines “Scope 1 emissions” and “Scope 2 emissions,” “respectively as a registrant’s direct emissions and indirect emissions largely from the generation of purchased or acquired electricity consumed by the registrant’s operations.”

Scope 1 and Scope 2 reporting requirements vary by entity.

- The new rule only requires large accelerated filers (LAFs) and accelerated filers (AFs) to report on Scope 1 and 2 emissions metrics. Registrants required to report on GHG emissions must also describe the methodology they used, including inputs and assumptions, to calculate such emissions. The rule states registrants may use “reasonable estimates” when reporting GHG emissions as long as they discuss the underlying assumptions and rationale for such estimates.

- Smaller reporting companies (SRCs) and emerging growth companies (EGCs) are both exempt from Scope 1 and 2 emissions disclosure requirements.

- Domestic filers must include this information in their annual report on Form 10-K, or in the issuer’s second quarter report on Form 10-Q for the fiscal year following the year in which the GHG emissions occurred.

- Foreign private issuers must include such information in an amended Form 20-F due at the same time such disclosure is due for domestic filers.

ii. Impact of Climate-Related Risks

The SEC’s new Climate Disclosure Rule requires registrants to disclose “any climate-related risks that have materially impacted or are reasonably likely to have a material impact on the registrant, including on its business strategy, results of operations, or financial conditions.” This obligation is intended to protect investors by informing them of the climate-related risks that may impact their investments. The Climate Disclosure Rule defines “climate-related risks” to mean those “actual or potential negative impacts of climate-related conditions and events on a registrant’s business results of operations, or financial condition.”

Registrants are required to report on two primary types of risks:

- “Physical risks,” including “acute” and “chronic” climate-related risks to a registrant’s business. “Acute risks” are defined as “event-driven risks [that] may relate to shorter-term severe weather events, such as hurricanes, floods, tornadoes, and wildfires,” while “chronic risks” are defined as risks emanating from longer-term weather patterns, such as sustained high temperatures, sea level rise and drought.

- “Transition risks” are defined as “the actual or potential negative impacts on a registrant’s business, results of operations, or financial condition attributable to regulatory, technological, and market changes to address the mitigation of, or adaptation to, climate-related risks . . . .” The rule provides several non-exclusive examples to illustrate the scope of the rule, including costs associated with changes in law or policy, reduced demand for carbon-intensive products and resulting losses, the devaluation or abandonment of assets, and risk of legal liability.

The Climate Disclosure Rule requires registrants to report on any climate-related risks that “have materially impacted or are reasonably likely to have a material impact on the registrant, including on its strategy, results of operations, or financial condition” in both the short-term, defined as in the next twelve (12) months, and in the long-term, defined as beyond the next twelve (12) months.

Registrants must also describe the actual and potential material impacts climate-related risks may or will have on each entity’s strategy, business model, and outlook, as well as the entity’s operations, products and services, suppliers, expenditures on R&D, and any other significant changes or impacts. In addition, the Climate Disclosure Rule requires registrants to discuss whether and how they consider the material impacts they disclose, including whether those risks are integrated into the company’s strategy, financial planning, and capital allocation, and whether and how such resources are utilized to reduce climate-related risks. If a registrant makes material expenditures that impact their financial estimates and assumptions that are the direct result of (a) efforts to mitigate or adapt to climate-related risks, (b) disclosed transition plans, or (c) disclosed targets or goals or actions to advance those targets or goals, they must provide a qualitative and quantitative description of those expenditures.

The SEC indicates that only material climate-related risks must be reported, a determination registrants must make themselves. However, the SEC also indicates that the inclusion of the term “material” throughout the rule was intended to evoke traditional notions of materiality in line with the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence on the subject.[3]

iii. Other Disclosures

In addition to disclosing new information concerning GHG emissions and new climate-related risks, the SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rule requires that covered registrants share certain other categories of climate-related information, including, among others:

- Climate-related Targets and Goals: Registrants are required to share any climate-related targets or goals they have developed, if such targets or goals have materially affected or are likely to reasonably materially affect the registrant’s business, results of operations, or financial condition. Those who disclose targets are required to explain the impact these targets are likely to have on one’s business.

- Internal Carbon Pricing: Registrants must report on their use of internal carbon pricing if it is material to how they evaluate material climate risks.

- Severe Weather Event Reporting: Registrants must report on any capitalized costs, expenditures expensed, charges, and losses incurred as a result of severe weather.

- Carbon Offsets and Renewable Energy Credits or Certificates: Registrants must report any capitalized costs, expenditures expended, charges, and losses related to carbon offsets of renewable energy credits or certificates ( both known as RECS) if they are material to a registrant’s disclosed climate-related targets.

- Safe Harbor Rule: The final rule extends safe harbor provisions from the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (PSLRA) to climate-related disclosures, other than historical facts, concerning transition plans, scenario analysis, the use of internal carbon pricing, as well as targets and goals. However, Scope 1 and 2 GHG emissions disclosures do not fall within any safe harbor.

B. Governance

The Climate Disclosure Rule also requires reporting entities to disclose information about how they govern climate-related risks in their respective lines of business. For example, the Climate Disclosure Rule instructs filers to “[d]escribe the board of directors’ oversight of climate-change related risks,” and “[i]f applicable, identify any board committees or subcommittees responsible for the oversight of climate-related risks and describe the processes by which the board or such committee or subcommittee is informed about such risks.” The Climate Disclosure Rule also mandates reporting on “management’s role in assessing and managing the registrant’s material climate-related risks.” This includes describing the management positions or committees (if any) responsible for overseeing climate-related risks, the processes such positions or committees oversee, and whether such positions or committees report this information to the boards of directors or their committees or subcommittees.

C. Implementation Process

The Climate Disclosure Rule will (absent potential court intervention, which is discussed below) become effective sixty (60) days after it is published in the Federal Register.

An individual registrant’s reporting requirements will phase in at different times over the next few years, depending on the filing status of the entity.

- All LAFs are required to:

- Make financial statement disclosures and all other disclosures, except material expenditures and impacts and GHG emission disclosures, by fiscal year beginning 2025.

- Make disclosures about material expenditures and impacts by fiscal year beginning 2026.

- Make Scope 1 and Scope 2 GHG emission disclosures by fiscal year beginning 2026.

- Make limited assurance attestation on Scope 1 and Scope 2 GHG emission disclosures by 2029 and a reasonable assurance attestation by fiscal year beginning 2033.

- All AFs (excluding SRCs and EGCs) are required to:

- Make financial statement disclosures and all other disclosures, except material expenditures and impacts and GHG emission disclosures, by fiscal year beginning 2026.

- Make disclosures about material expenditures and impacts by fiscal year beginning 2027.

- Make Scope 1 and Scope 2 GHG emission disclosures by fiscal year beginning 2028.

- Make limited assurance attestation on Scope 1 and Scope 2 GHG emission disclosures by fiscal year beginning 2031.

- All Nonaccelerated filers, SRCs, and EGCs are required to:

- Make financial statement disclosures and all other disclosures, except material expenditures and impacts and GHG emission disclosures, by fiscal year beginning 2027.

- Make disclosures about material expenditures and impacts by fiscal year beginning 2028.

The below table was provided by the SEC in conjunction with the Climate Disclosure Rule, indicating the applicable deadlines. It should be noted that the focus on fiscal years means that the earliest time that disclosures will likely be filed with the SEC is the 10-K that is filed in the subsequent calendar year — e.g., the 2026 10-K filed for fiscal year 2025.

| [4] |

III. Changes From Proposed SEC Climate Disclosure Rule (March 2022)

A. Overall Characteristics

The SEC extensively revised the rule it proposed in March 2022 to reflect certain themes from nearly 25,000 public comments. In general, these modifications tended to reduce the rule’s scope and provide registrants with more leeway on how to construct their disclosures while preserving the utility to investors.

A driving factor behind these changes seems to have been an effort to alleviate the burden of compliance on registrants charged with collecting and reporting on new information, achieved partly by reducing the number of specific prescribed considerations for registrants. The SEC also stressed its intention to ground the rule in traditional notions of materiality. This materiality emphasis may also serve to mitigate future legal challenges to the SEC’s statutory authority, a concern raised by many commenters. Indeed, the SEC assures that the rule serves the expressed need of investors for data on climate-related risk and that the Commission “remains agnostic” on wider environmental issues.

B. GHG Emissions

Given the unease of commenters and significant pushback from prominent politicians, the SEC significantly curtailed its reporting requirements for GHG emissions in the final rule.

Notably, the SEC removed Scope 3 emissions from the disclosure requirements. In its rationale, the SEC cited the lack of “current availability and reliability of the underlying data for Scope 3 emissions,” leaving open the possibility of Scope 3 GHG emissions disclosures in a future rule should the informational environment change. Additionally, the SEC exempted nonaccelerated filers, smaller reporting companies (SRCs), and emerging growth companies (EGCs) from any GHG emissions disclosure requirements in the finalized rule. Large accelerated filers (LAFs) and accelerated filers (AFs) (that are not SRCs or EGCs) will still be required to report on their Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, to the extent such emissions are material, as well as provide assurance and attestation.

Other changes have been implemented in the final rule to further reduce the burden of disclosure. Registrants have been afforded greater flexibility to determine the organizational boundaries within which they collect emissions data, instead of all assets listed in their financial statements. Disclosure requirements surrounding the methodologies used to capture their emissions data have also been reduced to require only a “brief description,” rather than detailed account, of the factors and calculations used.

Additionally, the SEC significantly eased the rigor of its data reporting requirements. Companies will only need to report emissions data in terms of aggregate CO2 emissions rather than relative intensity.[5] Requirements to break down emissions data by the amounts produced of each constituent gas have also been stripped from the final rule (although a description of the pollutants present will still be required).

C. Materiality

The Climate Disclosure Rule is expressly designed to elicit information about climate-related risks deemed material (i.e., information that a reasonable investor would view as significant for their decision-making). The draft climate disclosure rule lacked this specific materiality requirement, and commenters expressed concerns that the rule’s language, coupled with its extensive scope, could create confusion, resulting in an excessive amount of immaterial information provided as registrants grappled with the new reporting requirements.

To address this issue, the SEC added explicit materiality qualifiers — “have affected,” “are reasonably likely to affect,” and the like — within key provisions of the final rule. Further, language was also employed in other circumstances to focus on material issues — e.g., registrants will no longer be required to discuss the interaction between two material climate-related risks.

Notably, the SEC invoked materiality in the Climate Disclosure Rule in the context of climate-related risk disclosure. Contrary to the draft rule, registrants are only required to disclose information concerning their oversight of and adaptation to climate-related risks if a material effect on the company’s financial condition has occurred or is likely to occur. The same applies to information regarding the oversight of a company’s climate-related transition plans, expenditures, and methods used to compute the presence of risk.

D. Governance

Compared to the original proposal, the final Climate Disclosure Rule significantly reduced the extent of the reporting requirements with respect to corporate governance and climate risk. Several notable disclosure requirements that were the subject of concern in the comments were dropped from the final Climate Disclosure Rule. These included highly specific queries concerning corporate governance, including: (1) the identity of specific board members responsible for climate-risk oversight; (2) whether any board member has expertise in climate-related risk; (3) how frequently the board is informed of climate-related risks; and (4) how climate-related targets or goals are set by the board. These have been replaced by far less prescriptive reporting requirements, which only seek information about the responsible board committee or subcommittee, and the processes by which that body is informed of climate-related risk.

Further reflecting these concerns, the SEC also has incorporated a materiality qualifier for disclosures concerning how a company identifies, assesses, and manages climate-related risk.

E. Extended Phase-In Periods

The Climate Disclosure Rule provides for an extended phase-in period for the reporting requirements. Under the draft rule, large accelerated filers (LAFs) were obliged to begin reporting Scope 1 and Scope 2 GHG emissions by FY 2023 and to provide limited assurance the year following (FY 2024) as well as reasonable assurance two years after that (FY 2026). Accelerated filers (AFs) had a similar schedule, merely delayed by a year.

Under the final Climate Disclosure Rule, the initial compliance deadline to begin reporting Scope 1 and Scope 2 GHG emissions has not only been delayed by the two years that have elapsed since the issuance of the draft rule, but the timeline itself has been extended, with most deadlines doubled, providing registrants with an additional opportunity to develop the processes and procedures necessary to comply. LAFs now have two years before they are required to report Scope 1 and Scope 2 GHG emissions (FY 2026) — and AFs have fully four years (FY 2028) before they are subject to those requirements. Similarly, both LAFs and AFs have three years from their initial reporting of Scope 1 and Scope 2 GHG emissions before they are required to offer “limited assurance.”

F. Carbon Offsets and Renewable Energy Credits

Following these general trends, the disclosure requirements for the use of carbon offsets and renewable energy credits (RECs) have also decreased. Companies will no longer be required to disclose any use of carbon offsets or RECs that merely have a role in the company’s climate-related business strategy. Rather, under the final Climate Disclosure Rule, companies must only disclose carbon offsets or RECs if they have been used as a material component of a plan to achieve climate-related targets or goals.

IV. Political Issues

The promulgation of the Climate Disclosure Rule has been politically fraught. A number of influential senators — not only prominent Republicans but also those aligned with the Democratic Party, such as Jon Tester (D-Montana) and Krysten Sinema (I-Arizona) — raised concerns about the nature and scope of the proposed climate disclosure rule. And beyond Congress, the media discourse has been far from uniformly positive. Indeed, as demonstrated by the public comments published on the SEC’s website, even those individuals and organizations that generally support the SEC’s efforts with respect to climate disclosure had significant reservations about different provisions of the draft rule, many of which have been addressed by the final Climate Disclosure Rule (e.g., removing the disclosure requirement for Scope 3 GHG emissions).

This challenging dynamic means that the Climate Disclosure Rule is politically vulnerable and could be effectively overturned by a subsequent presidential administration that is less enamored with or focused on the intersection between financial reporting and environmental concerns.

A. Legal Challenges

Beyond political considerations, there are also a number of significant legal issues, which could impact whether the SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rule will ever be enforced. The Climate Disclosure Rule will be — and indeed, already has been — challenged in the courts. Ever since the draft rule was first issued by the SEC, there has been considerable criticism of the legal foundation of the proposed rule, in particular that it was beyond the scope of the SEC’s power (i.e., ultra vires). These criticisms were proffered by conservative commentators as well as by the Republican SEC Commissioners themselves. Indeed, Commissioner Uyeda’s statement when the SEC published the final Climate Disclosure Rule effectively provided a roadmap for future legal challenges, as he stated that the Climate Disclosure Rule violated “the major questions doctrine,” raised “concerns about [the SEC’s] statutory authority,” and noted that “the Commission conducted a flawed process.” It is safe to assume that these legal critiques will feature in the inevitable challenges to the Climate Disclosure Rule.

In fact, on the very same day that the SEC issued the Climate Disclosure Rule, 10 US states[6] filed a petition for review in the Eleventh Circuit challenging the Climate Disclosure Rule. Specifically, these states argued that “the final rule exceeds the agency’s statutory authority and otherwise is arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, and not in accordance with law.” Subsequently, two additional groups of states filed similar petitions for review, in the Eighth Circuit[7] and Fifth Circuit.[8] Similar lawsuits have also been launched by trade associations in the energy sector, including the Texas Alliance of Energy Producers. It should also be noted that the US Chamber of Commerce has taken a leading role in challenging California’s state laws concerning climate-related disclosures, and either the Chamber of Commerce or a similarly situated group of business organizations will probably file suit here as well.

Environmental organizations, such as the Sierra Club and Sierra Club Foundation, have also mounted legal challenges based upon the contention that the Climate Disclosure Rule is inadequate to provide investors the needed information regarding climate change to make fully informed investment decisions.

V. Conclusion

The Climate Disclosure Rule represents a profound shift in the SEC’s disclosure regime. Climate-related financial disclosures will now be mandatory for public companies participating in the US capital markets. Even though the scope of the Climate Disclosure Rule has been significantly reduced from the contents of the draft proposal, the very fact that the Climate Disclosure Rule has been issued is a significant change in the SEC’s reporting requirements.

Moreover, even if the Climate Disclosure Rule is ultimately overturned by the courts, the SEC has now indicated the nature and extent of what it believes are the necessary climate-related disclosures. It is altogether possible that companies will begin adhering to this regulatory standard, even if not compelled to, for ease of operating in the markets (e.g., the comparability of different companies’ disclosures). Companies may also update their understanding of materiality based upon this rule — i.e., considering the extent to which climate issues materially impact the business and operations of the company — which would also be reflected in corporate disclosures. The SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rule has now inarguably set a new standard for climate-related financial disclosures for US companies. This benchmark will profoundly shape the regulatory landscape in the United States.

Thanks to Mintz Project Analyst Tucker Kelsch for his significant contributions to this memo.